The seed for this series was planted in the winter of 2021. The director a community agency with whom I’d done some freelance teaching and organizational consulting asked if I’d be interested in developing a Black History Month presentation to help fulfill a grant requirement. The grant involved working with at-risk middle school students in an after-school program.

The agency had ample access to prepackaged resources for the 10 participating schools, but the director wondered if, instead, I could create a more personal, interactive perspective. A more personal presentation would be especially helpful since the students were still struggling with face-to-face communication after being confined to digital classrooms because of the COVID pandemic.

The task seemed daunting, yet exciting…middle schoolers notwithstanding.

A few years earlier, the director had seen a program my wife and I created and performed through our performing arts company, Kingdom Impact Theater Ministries. The piece, “Freedom Song,” is scenes and monologues depicting how Biblical scriptures influenced the music that inspired slaves, people who battled slavery and segregation, and those who fought for civil rights. “Freedom Song” then raises the question:

Where is such Biblical influence today among movements as Black Lives Matter, The 1619 Project, Critical Race Theory, and even in the debates about whether Black history should even be taught in schools?

Having seen our show and serving on committees together, the director seemed confident I could downplay any controversies by sharing anecdotal experiences as well as facts.

Our interactions revealed my passions for active history — touring museums and historical sites, photographing artifacts; also my love of historical reading — biographies and the historical markets in parks, buildings and roadsides (to the bane of my Can-we-go-now? offspring).

Then there was the benefit, not mentioned but politely acknowledged, of my age.

My life as a journalist, actor, educator, and pastor has spanned decades of lived black history. My siblings and I inherited a storytelling gene from our parents that can sometimes younger people can find intriguing. Provided our tales are designed for Short-Attention Span Theater, students might find them fun to discuss. If not fun, then an educational diversion from the regular assignments — a perspective I find ironic. Few individuals living those moments found them either fun or historical. They saw them as “surviving.”

The “fun” factor sometimes is the disbelieving awe with which students respond to tales of segregated swimming pools, class rooms, or dating. The more such stories are shared, I find less fun and more irony I find, especially in light of hubbubs about schools exploring Black history, or any other cultural history for that matter.

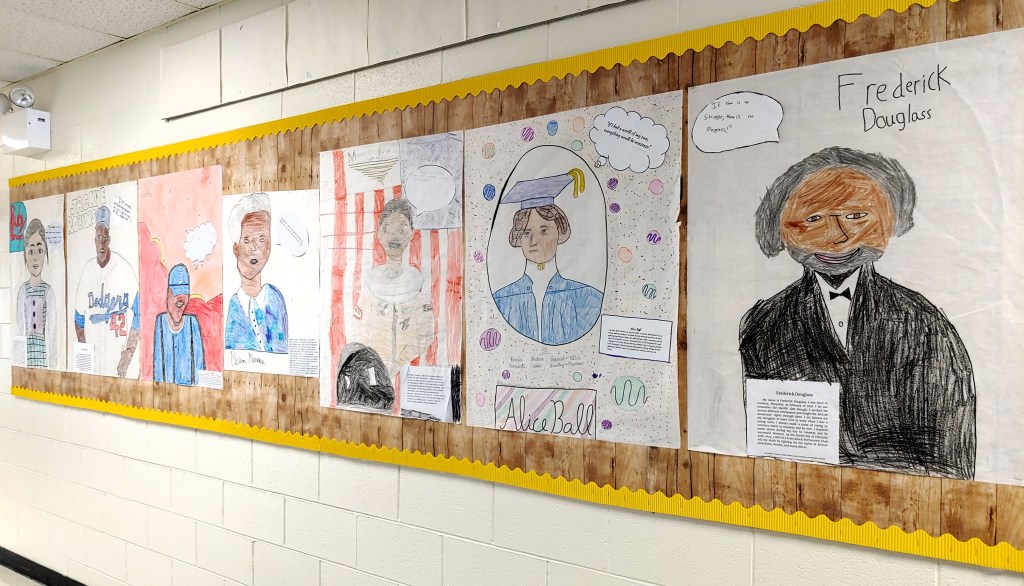

There is irony that tales of individuals who survived life-threatening experiences have become fodder for school textbooks adoptions, homeroom art displays, or political grandstanding. For among the ironies is that the primary battleground about teaching Black history is the very source that contributing to Black history: the schoolrooms of America.

Irony, as you’ll discover in these stories, is among my favorite forms of humor, though irony’s foundation is Greek tragedy. Humor, as we’re discovering, is a quintessential yet endangered survival skill. Black history abounds with irony.

My approach was not to laden students with just facts and figures — they’d get those elsewhere from more instantaneous instructors and resources. Just ask Google or Alexa. Right, Siri? (When in doubt, there’s always Wikipedia.)

I prepared my outline to integrate the data with categories tied to academic topics as STEM, English Language Learning, and Social Emotional Learning. This involved reflecting on cultural attitudes or systems during specific eras that affected Black individuals, and the methods which Blacks in those eras used to withstand or alter those attitudes or systems.

Aside from historically recorded tales, I recalled how many of these attitudes and methods came from pieced-together family experiences. Both my blood-kin and married-into families are microcosms of how global “Black History” may have impacted individual households, factors overlooked in, say, Congressional or PTA hearings. I shared personal stories for several reasons:

- I trusted this structure would allow the ethnically mixed classrooms of United Nations demographics to gain greater appreciation for Black History Month;

- I hoped my memories would illustrate racial growth that has occurred throughout U.S. history, and therefore, rather than getting stuck replaying past horrors, they’d see examples and hope to overcome aspects of race relations that are woefully unchanged or, sadly, have regressed in my lifetime;

- I believed the diverse student bodies of my classrooms might help them see more similarities of struggles, dreams and values, than superficial differences;

- Finally, I envisioned that our discussions might provide a template for their own research as they developed a passion for exploring their own family legacies before visiting Ancestry.com.

Leave a comment