Amid the roses, candy, flowers and candlelight dinners you’re gathering for February 14, remember to get a birthday cake and candles. The cake should have Kente colored icing and 206 or 207 candles. Oh, and two cards for the honoree: one on write, “Happy Birthday, Frederick.” On the other, “Thank you for Black History Month.” Sign it, “We, the people.”

Now, regardless of your position on whether or not Black History ought to be a course taught in schools, or the merit of celebrating African-American contributions to the U.S. for 28 days — sorry, 29 days (leap for joy, yeah!) — even the most casual observer of American history ought know the influence of the man dubbed Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey as a slave at birth who renamed his freed self Frederick Douglass.

Although yet to have been the subject of a Hollywood bio-pic, Douglass’ life as a former slave, escape to freedom, and subsequent abolitionist career as journalist and international speaker is essential study for anyone interested in the complex American trinity of justice, patriotism and religion.

Douglass’ autobiographies, speeches and influence so moved historian Dr. Carter G. Woodson, that when Woodson — a first-generation freed offspring of former slaves — sought a specific timeframe he believed Negro history ought be taught in schools, he focused on the date Douglass chose for his birthday, February 14. Noting that Douglass’ birthday was two days after that of President Abraham Lincoln, February 12, Woodson chose to honor the two men most responsible for ending slavery in the U.S. Accordingly, in 1926 Woodson deemed that the second week of February be designated “Negro History Week.”

That’s what February’s annual celebration was called when 10-year-old me first became aware that people like me (“Negroes,” then), were actually part of U.S. history. This was 1963, a month after we learned that 100 years earlier the Emancipation Proclamation was issued, seven months before we had any idea Martin Luther King marched and dreamed.

It wasn’t until my last semester of high school that a class about historical Negroes became part of the school curriculum. By then, we “Negroes” were becoming “Black,” but the class couldn’t be called “Black History” yet. So the instructor who devised the course, a white teacher (Jewish, actually) born in Brooklyn, named it “Values and Issues.”

The year after I graduated college, enough world-shattering events involving colored people had occurred among Blacks in my lifetime and the 50 years since Woodson created the course, that studies expanded beyond the classroom and into the culture known as “Black History Month.”

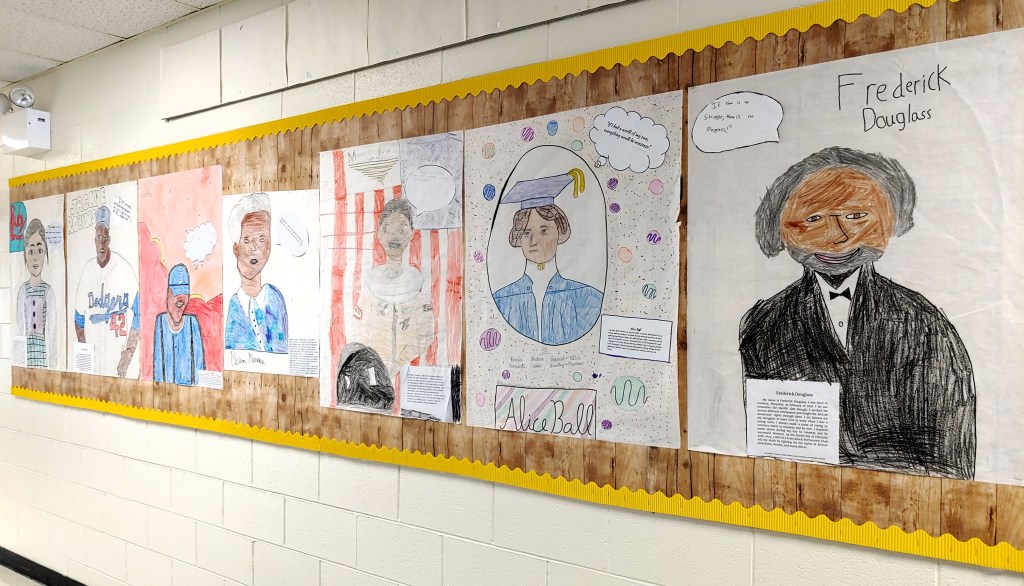

Throughout the titular changes in the studies (including the era of “African-American History Month”), the importance of Frederick Douglass has remained unchanged. If anything, recognitions of his life have more embodied Woodson’s ultimate dream for exploring Negro history: that its lessons and contributions not be confined to a separate course of study, but infused into the regular curriculum alongside the issues of other people groups who have shaped this nation’s values.

Of the monuments, buildings, schools and parks honoring Douglass throughout the country, perhaps none more personifies Woodson’s dream of historical inclusion than the Freedom Shrine in National Harbor, MD. A statue of Douglass boldly stands along side Presidents Washington and Lincoln beneath an American flag that anchors a walkway of influential, freedom-fighting Americans.

Touristy and romantic as the statues may seem, including Douglass in a public setting achieves what historic art should: spark conversation about the real person and period the person lived. Douglass’ life is the quintessential story of Blacks in America before Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation: a life born into slavery, a broken family and search for identity.

Leave a comment