Presidential Fun Facts…well, maybe not FUN, but inFUNmative:

Of the first 18 Presidents of the United States, 12 owned at least one Black slave during his lifetime. See for yourself.

What do you do with that information?

By today’s standards of cancelling past actions (sins?) of well-known people, would we eradicate every statue, library, street named for these individuals?

Do we take a look at the six men who did NOT own slaves and rate them as more honorable, perhaps overlooking other faults?

And what of the African-Americans who also owned Black slaves? Is there an element of self-loathing? How do we relate to Native American slave ownership? Does that create racial animus to be recognized or ignored?

Or do we, recognizing the life of the nation during that era, take a closer look at the effect slavery ownership had on the men personally, or influence on his policies in and out of office?

For example, a look at how the non-slaveholding presidents from the Adams family — John, the second president; and his son, the sixth President, John Quincy Adams — wrestled with the issue of slavery.

After losing his Presidential re-election bid to Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams became known for two bold anti-slavery actions. The first was after he became the only President to return to Congress when citizens of Massachusetts elected him to a seat in the U.S. House (1830-1848). In Congress, he fought to repeal the “gag rule,” which prohibited the discussion of slavery on the House floor.

LEARN MORE: “John Quincy Adams and ‘The Gag Rule’ “

The second was in 1842: Adams was asked to argue a case before the U.S. Supreme Court regarding a revolt by natives of Mende from the West African nation of Sierra Leone. They had been captured by Portuguese slave traders and were being taken to Cuba on the ship Amistad. The slaves overtook the crew of the Amistad to force them to return to Sierra Leone.

Instead, a navigator steered the ship north to America where the Amistad was captured by the U.S. Navy. Though the government dropped murder charges, the rebels remained imprisoned. Adams and the Attorney General debated whether the rebels should be returned as property to the expectant slave owners in Cuba, or returned to Sierra Leone as freedmen.

READ MORE: The Amistad Case | National Archives

READ MORE: Cinque the Leader

READ MORE: John Quincy Adams and the Amistad Event

“The Constitution of the United States recognizes the slaves, held within some of the States of the Union, only in their capacity of persons,” Adams argued. “The Constitution no where recognizes them as property. The words slave and slavery are studiously excluded from the Constitution. Slaves, therefore, in the Constitution of the United States are persons, enjoying rights and held to the performance of duties….”

Adams won the case and the freed Mende residents returned to Sierra Leone.

Fighting an unpopular legal battle in American courts seemed an Adams family value. John Quincy’s father had become ostracized and respected when he successfully defended British soldiers charged with instigating the Boston Massacre in 1770.

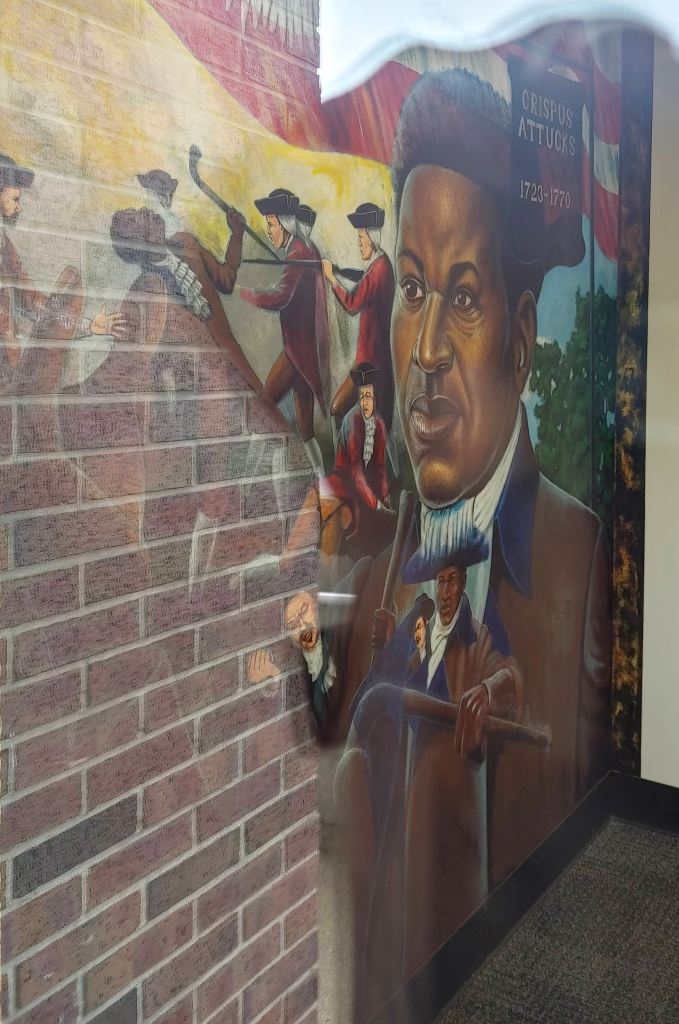

Among the five colonists killed was Crispus Attucks, a Black and Native American merchant seaman. A freeman. Many historians say that Attucks was the first fatality of the Massacre and, as such, a symbol of America’s racial irony. Schools, statues and community centers named for Crispus Attucks through the U.S. frequently point out that a Black was the first to die for the freedom of a country in which he could not be free.

READ MORE: Boston Massacre: Causes, Date & Facts | HISTORY

READ MORE: Crispus Attucks – Facts, Boston Massacre & American Revolution

That twisted irony was a dominant dilemma in most of the 28 Presidential administrations after the Civil War ended in 1865. Ten of those Presidents had unique opportunities to influence Black History during his term in office. Their influence ranged from positive or negative legislative action to altering or reinforcing Black stereotypes.

None of the decisions of the ten was easily enacted or popular. No choice was clearly black and white, so to speak. This is the case even in our times in which, depending upon our look at history as revisionist or judgmental, we tend to view racially influential Presidential decisions as acceptable or insincere.

No commander-in-chief articulated the vacillating quagmire of Presidential blackness in which Founding Fathers trod than President John Adams in 1801. Adams was anti-slavery, but also anti-abolition. He considered abolitionists instigators of violence, and the Abolition Movement dangerous to the nation. He intimated as much responding to two abolition leaders who asked him to clarify his position on slavery.

“Although I have never Sought popularity by any animated Speeches or inflammatory publications against the Slavery of the Blacks,” Adams wrote, “my opinion against it has always been known and my practice has been so conformable to my sentiment that I have always employed freemen both as Domisticks and Labourers, and never in my Life did I own a Slave.

“The Abolition of Slavery must be gradual and accomplished with much caution and Circumspection.”

Adams, whose life in New England was far removed from plantation affairs in the South, continued with a perspective that could be likened to modern viewpoints of suburban or rural residents who have limited interaction with urban affairs. Although the slave industry in 1800 America was growing, Adams continued:

“There are many other Evils in our Country which are growing, (whereas the practice of slavery is fast diminishing)… These are in my opinion more serious and threatening Evils, than even the slavery of the Blacks, hateful as that is.

“I might even add that I have been informed, that the condition, of the common Sort of White People in some of the Southern states particularly Virginia, is more oppressed, degraded and miserable than that of the Negroes.”

READ MORE: John Adams on the abolition of slavery, 1801

Leave a comment