Decades later, another geographically removed president, New Yorker Martin Van Buren held a similar hands-off, anti-abolitionist point of view. Van Buren had inherited one slave long before he entered the Presidency. When the slave ran off, Van Buren made no effort to run him down, considered a passive-aggressive approach to abolition.

As President, Van Buren was more actively anti-abolition. An example was when he ordered his Attorney General to side with Spain to extradite the Amistad rebels mentioned earlier. This led to the Supreme Court case that John Quincy Adams fought and won.

READ MORE: Martin Van Buren – Wikipedia

Out of office, Van Buren opposed the expansion of slavery into the Western territories, a core issue in the impending War Between the States facing one of his successors, another conflicted non-slave holding president, Abraham Lincoln.

While it’s true Lincoln has been revered, with much justification, as the man who purportedly “freed the slaves” by issuing the Presidential Executive Order known as the Emancipation Proclamation, and for his political astuteness (trickery?) to push for the 13th Amendment to abolish slavery, Lincoln is often criticized for not being the believer in Black equality many think he was. (A similar later criticism of John Kennedy.)

The Lincoln critique comes from private papers and public statements that depict his language and views of Blacks that are often similar to the negativity of the time. His most conflicting statement was his private response to an editorial written by Horace Greeley in the New York Tribune in August 1862. Greeley had criticized Lincoln for foot-dragging on the issue of slavery. Part of Lincoln’s response said this:

“If I could save the union without freeing any slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that.”

READ MORE: Lincoln’s Slavery Conflict

READ MORE: Lincoln’s Private Letter to Editor Horace Greeley

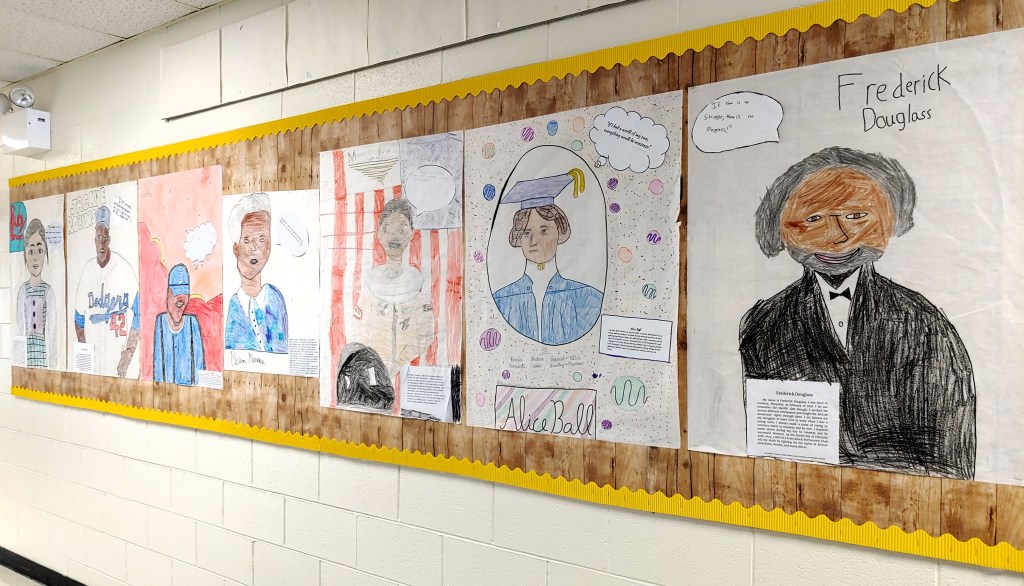

This viewpoint, and the fact that the Emancipation was limited in scope and took time to enact, are reasons many historians underplay his standing as “The Great Emancipator.” Not just historians, but his contemporaries. Frederick Douglass, for example, who supported Lincoln’s original candidacy for President withdrew his endorsement in 1864, believing Lincoln’s methodic emancipation process contradicted his 1860 promises.

However he came to the decision, Lincoln, nevertheless, took a civil rights stand no other President did…and that few have since. While on the way to become what I’ll call “The Eventual Emancipator,” given that did so by re-uniting the U.S.A, perhaps a better nickname for Abraham Lincoln is “the step-father of our country.”

If so, that begs the question: How much have Lincoln’s White House successors been in step with resolving issues facing Black Americans in our country?

Leave a comment