The end February comes with mixed emotions. The month began looking forward to celebrating February’s special events, daily or month-long endearing holidays. Groundhog’s Day. Valentine’s Day. National Battery Day. Depending upon your perspective and budget, you approached the festivities with great expectations.

Or with grate expectations.

It’s not mentioned often (not aloud, anyway) but if we’re honest, we would admit there are places where Black History Month grates on the nerves, and its conclusion is greatly anticipated. Great news: February ends; Black history continues; the people aren’t leaving. Ah, there’s the rub!

Among the most disappointing developments of my life has been watching the evolution of negativity toward Black History Month and the daily animus spewed from high levels of government to small classroom gatherings.

The back-and-forth viewpoints that appear in my email boxes, social media crawls, or midday conversations sadden, yet amuse me.

Part of my amusement is that I occasionally reflect on how often similar comments have fallen upon my ears over the years.

Part of my sadness is that I occasionally reflect on how often similar comments have fallen upon my ears over the years.

The Purpose

Whatever your personal perspective about the necessity of teaching Black History, here is a takeaway I’m hoping readers grasp in these essays. These writings build on the purpose of study of the genre as expressed by Dr. Carter G. Woodson, the Father of Black History, who began the February academic ritual in 1926. The first-generation freed son of slaves, Woodson established the study of Black history for two reasons:

- One: Personal Pride — to show ex-slaves, like his parents, that the people of African descent made significant contributions to global civilizations, and specifically American civilization, in roles other than as slaves.

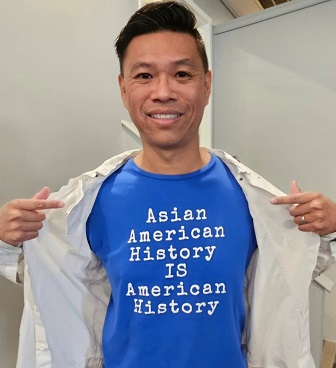

- Two: Global Unity — to set a foundation for the contributions of other ethnicities in the United States to be woven into the tapestry of American history curriculums rather than as separate footnotes.

Said Woodson: “What we need is not a history of selected races or nations, but the history of the world void of national bias, race hate, and religious prejudice.”

A paradox of debates and celebrations about Black History is that the opposite has occurred. The conceit of Black History Month has inspired similar celebrations such as Asian Pacific American Heritage Month (May), National Hispanic American Heritage Month (Sept. 15-Oct. 15), Native American Heritage Month (November). Rather than embrace those individual cultural tales into the fabric of teaching American history, they often seem asides. Moreover, from my observations, none of the cultural outreaches of the other people groups have merited gubernatorial intervention, school board protests or accusations of indoctrination as with Black History Month. Asking “Why?” is among purposes of the blog series.

There’s another paradox of the current Black History conundrum. The evolving identity of me, myself and my contemporaries.

VIEW VIDEO: “Far East Deep South,” documentary of a Chinese man who find his Mississippi roots

The Middle (School) Ages

When I was in what’s now called middle school, the Mason-Dixon line of academic debate, we didn’t have Black History Month. We weren’t even Black, in a positive vein. We were still Negroes, and according to books that I remember we had available in the classroom, our history (we thought) only filled five days of the curriculum. So we, at the all-colored school, just learned about us during Negro History Week.

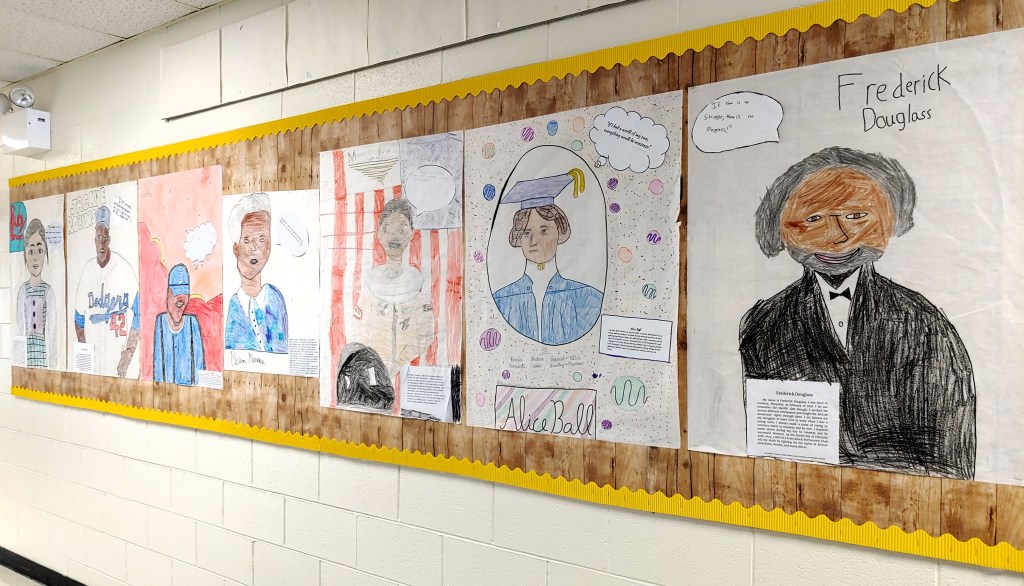

Negro History Week was such a novelty that when an elementary teacher at the school I attended coordinated a Negro History Week display in a main hallway, our well-connected principal arranged for the city’s major morning newspaper to send a photographer to share with images with the entire populace of Indianapolis.

I don’t recall the display, teacher or photo. All appeared at my school the February 15, 1968, after I’d graduated. But I DO remember the principal, Mr. (Leonard) Glover, a lanky, sharply-attired figure who was both a symbol of respect and target for teasing for the daring dudes. Mr. Glover’s stature managed the student body with little effort, be it towering above everyone strolling through the halls, or engaging his powerful basso profundo to quell lunchroom disturbances. And with the snap of his fingers (as in, “Hey, hey, hey, buddy!” Snap! Snap! Snap!) order was restored (giving my impressionistic buddies another mannerism to impersonate).

Though buried on Page 43 of The Star, the photo made an impression on someone in our household who clipped the picture and put it a file. Who saved the photo is less relevant than that I found the clipping 56 years later, several months after originally posting this story. I was weeding files I’d salvaged from a basement flood. Untouched by water, hey, hey, buddy! Up popped Mr. Glover, the Teacher-Whose-Class-I’d-Never-Have-Cut, and two students, posing before posters of four living Negroes who had made recent history. None of them was Martin Luther King. He wouldn’t become history until two months later when he was assassinated.

Clipping the photo might have been something Dad did. It might have been me, excited to see Mr. Glover. The point being, Negroes of a certain era did that when a photo of someone we knew appeared in the paper without being related to a crime. Pride by association. I think that was part of Carter Woodson’s point that’s gotten lost.

My grade school, Benjamin Franklin No. 36, where I was introduced to Negro History Week. The building is now part of an apartment complex. The Indianapolis Star photo I found of the “news-making” Negro History Week display at the school, February 15, 1968. Two months later, Martin Luther King was killed and Negroes started becoming Black. Photo (c) Michael Edgar Myers

What we were to discover, as time passed, as high school encroached and we Negroes became “Black,” was that events were happening around us cocooned in my Central Indiana all-colored-kids school rooms. Within a decade, those events would become fodder for textbook pages and bulletin board displays of schools across the U.S. We were living the history that is now causing apoplexy in statehouses, and White Houses, coast-to-coast. History does repeat. Or regress. That’s a reason what’s happening anew is painful.

SUGGESTED READING: “The Mis-Education of The Negro,” by Carter G. Woodson

At the same time, living through that history and seeing changes has been encouraging. For example, relatives dating or marrying “outside of their race” without fear of being ostracized or lynched. The mixed emotions that a Black man hosted the Oscars while remembering when there was only ONE Black actor in Hollywood! Then, another emotional spin seeing the Black man host, slapped by another Black man, who had been nominated for Best Actor…all within moments of an Oscars memorial to The ONE Black actor who received the Best Actor award! Now, THAT was Black history progress on national TV! Ed Sullivan, where for art, thou?

My “Personal Journey” is a combination of historical research and opinions based upon my experiences and travels. Although I started publishing in February, the series is not confined to Black History Month reading. Indeed, its structure fits more along the lines of both Woodson and a few of my friends who are White, and who are perplexed as to the need for such studies. The paraphrased summary of each viewpoint is, “History is history.” While that’s true, telling of history also involves the hearts of the people recounting the details as well as those listening.

When it comes to the stories about people of African descent, or other cultures of color who helped shape the United States, the most prevailing voices I often hear are Tom Cruise and Jack Nicholson in their climactic scene in “A Few Good Men:”

CRUISE: I want the truth!

NICHOLSON: YOU CAN’T HANDLE THE TRUTH!

Engraved on a monument to Carter Woodson in the park near his home in Washington, D.C., are his words, “Truth comes to us from the past, then like gold washed down from the mountain.”

Leave a comment